- I have always heard good things about the NYU Interactive Technology Program, and this wii-powered large-scale drawing tool for wheelchair users sounds awesome.

Digital Wheel Art from YoungHyun Chung on Vimeo.

via Wheelchair Dancer, who got a little test drive. The video is of a young man in a power wheelchair, moving back and forth controlling brightly colored lines across a digital canvas. At one point he says (subtitled) "I know what I am gonna do."

- I love people who use stuff and redesign that stuff to make it work better.

Vietnamese pedicab driver designs a better pedicab that (via Core77) "resembles a bicycle making love to a wheelchair."

- New design doesn't always fit old infrastructure.

The NY Times hits the hard issues: when ergonomic toothbrushes don't fit in ye olde toothbrush holder.

- Is the iPhone less usable for women because of "the fingernail problem"? (via UnBeige, who seem unnecessarily snarky about it. Only yokels complain about bad design?)

A blog about universal and accessible design

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

democratic cities

I feel like there has been a lot in the press lately about urban design and the "democratic" city. One of the endless fascinating things about urban life is how it is both public and private, accessible and inaccessible. The city for Baudelaire's flâneur is all about roaming about and being inspired, titillated, and entertained by the people and places of the city. I always felt as a longtime New Yorker that I am never alone as long as I have the city streets. But of course, the city has its flip side-- you can see and be seen, but you can also see where you are not welcome, or be seen in an unpleasant way, stared at out of curiosity, fear, or horror, or shoved out because you don't belong.

- In the Doors of Perception blog, an interview between John Thackera and Sunil Abraham is mainly about eco politics and sustainability in building cities. They emphasize a balance between speed and "slowth" (must be a british thing), not abandoning all goals of modernity and efficiency, but emphasizing local resources and measured mobility alongside speed of information. Their comments on urban planning as a government/commerce project are great:

JT. Show me a city with a “dynamic image” and I will show you an unsustainable city. “Dynamic” usually means high entropy buildings, financial speculation on a massive scale, and a low degree of social participation. From now on, the most interesting cities will be those whose citizens are able to invest their energy and creativity on “re-inhabitation” within the unique ecosystems of their place. This approach will often involve adaptive or more intense uses of existing infrastructure rather than the construction of signature buildings - and sometimes this approach will mean building nothing, nothing at all. To live sustainably we need to place more value on the here and now: a lot of destruction is caused when design is obsessed with the there, and the next - and the “dynamic”.

SA. First, the dynamism of a city can be found in the informal sector which in most developing countries accounts for 70% of employment. It is also where legal, technical and market limits and norms are challenged and redefined as everyday practice. The informal economy also has a much lighter infastructure. [...]

This last comment strikes me as so smart-- all the action is in the "informal sector" where streamlined resource use is not about "efficiency" or government protocol, but about reality. This "informal economy" is also run by personal relationships, not bureaucracy:

[SA continues]: ...non-market micro-economies such as gifting, barter, collectives and commons in developing countries are more effective than classical development interventions in addressing problems of social development. For example, home-based care is cheaper and more effective than hospice-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS. I would like to see more celebration of the informal sector, informal practices and non-market micro-economies.

- On a way fluffier note, the weird NY Times T Magazine style blog had a post about "off-limits" NY places. It is probably true that being hard to get into increases the "magnetism" of some spaces-- this is the whole model on which social clubs are based, right? I was glad to see a lengthy comment bemoaning the "travesty" of having so many architectural wonders of NY as spaces only for the rich. No mention of wheelchair accessibility (unsurprisingly) but I was thinking about what kind of exclusivity physical inaccessibility makes. When I walk around New York, I am often aware of how style and physical access are twinned, that high-end places often involve some form of physical venture to get into-- made all too clear to me, for example, when I mistakenly took my nonogenarian grandmother to a gorgeous, exquisitely designed vegetarian Korean restaurant where the seating was on the floor with legs shoved into a recessed hole under the table. Is a lack of ramp, or a narrow dark passageway, or the big heavy door at so many galleries and fancy stores, the same kind of message as a bouncer or the ubiquitous "girl with a list" at NY parties (or so I see when I walk by them)? It's a bit different, to be sure. Maybe it's more about asking you to feel unsafe for a second, increasing the "magnetism" via risk and fear? The more I look the more i think that the whole high-end fashion/design world is about this-- making you feel uncomfortable as a gateway. Ugh.

- In the Doors of Perception blog, an interview between John Thackera and Sunil Abraham is mainly about eco politics and sustainability in building cities. They emphasize a balance between speed and "slowth" (must be a british thing), not abandoning all goals of modernity and efficiency, but emphasizing local resources and measured mobility alongside speed of information. Their comments on urban planning as a government/commerce project are great:

JT. Show me a city with a “dynamic image” and I will show you an unsustainable city. “Dynamic” usually means high entropy buildings, financial speculation on a massive scale, and a low degree of social participation. From now on, the most interesting cities will be those whose citizens are able to invest their energy and creativity on “re-inhabitation” within the unique ecosystems of their place. This approach will often involve adaptive or more intense uses of existing infrastructure rather than the construction of signature buildings - and sometimes this approach will mean building nothing, nothing at all. To live sustainably we need to place more value on the here and now: a lot of destruction is caused when design is obsessed with the there, and the next - and the “dynamic”.

SA. First, the dynamism of a city can be found in the informal sector which in most developing countries accounts for 70% of employment. It is also where legal, technical and market limits and norms are challenged and redefined as everyday practice. The informal economy also has a much lighter infastructure. [...]

This last comment strikes me as so smart-- all the action is in the "informal sector" where streamlined resource use is not about "efficiency" or government protocol, but about reality. This "informal economy" is also run by personal relationships, not bureaucracy:

[SA continues]: ...non-market micro-economies such as gifting, barter, collectives and commons in developing countries are more effective than classical development interventions in addressing problems of social development. For example, home-based care is cheaper and more effective than hospice-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS. I would like to see more celebration of the informal sector, informal practices and non-market micro-economies.

- On a way fluffier note, the weird NY Times T Magazine style blog had a post about "off-limits" NY places. It is probably true that being hard to get into increases the "magnetism" of some spaces-- this is the whole model on which social clubs are based, right? I was glad to see a lengthy comment bemoaning the "travesty" of having so many architectural wonders of NY as spaces only for the rich. No mention of wheelchair accessibility (unsurprisingly) but I was thinking about what kind of exclusivity physical inaccessibility makes. When I walk around New York, I am often aware of how style and physical access are twinned, that high-end places often involve some form of physical venture to get into-- made all too clear to me, for example, when I mistakenly took my nonogenarian grandmother to a gorgeous, exquisitely designed vegetarian Korean restaurant where the seating was on the floor with legs shoved into a recessed hole under the table. Is a lack of ramp, or a narrow dark passageway, or the big heavy door at so many galleries and fancy stores, the same kind of message as a bouncer or the ubiquitous "girl with a list" at NY parties (or so I see when I walk by them)? It's a bit different, to be sure. Maybe it's more about asking you to feel unsafe for a second, increasing the "magnetism" via risk and fear? The more I look the more i think that the whole high-end fashion/design world is about this-- making you feel uncomfortable as a gateway. Ugh.

brand new blog manifesto

So, time to write a bit about what this blog is about. This is my Right to Design Manifesto.

I chose this title for my blog that because it makes sense to me to describe the kind of design and design issues I am following. So:

- First, it is kind of a question. Do we have a right to design? That is, do we have a right to designed things that fit us, that work well, and that are comfortable? When is bad design a violation of civil rights or human rights? A sociologist met recently pointed out to me that current disability law is one of the only official avenues of citizen complaint about poor public design. Even twenty years after the ADA, though, these questions are somewhat unresolved in the terminology of “reasonable accommodation.” I think of the “right to design” as a question, a provocative idea that prods us to ask what rights are, and also how design works to provide or block access-- not just to buildings or places, but to experiences that we might define as part of citizenship.

- Second, there is “the right to design” as a verb. Do we have a right to design things, to demand to make our own world different? This part of the argument comes out of years of observing and participating in debates around sustainable, social, and universal design. A lot of designers want to integrate these alternative, progressive ideas into their practice, but they can’t because their clients are not interested, considering these approaches to be unmarketable, or because they don't pass the tests of contemporary aesthetic or intellectual design practice. I, too, have often fallen into the rut of pessimism, thinking when I see a really great prototype or student design project, ‘well, that’s great but it will never get made.”

The way design appears in our current world is as commerce. Design is fashion, is consumption, is the latest desired object. This is indeed one part of design, but it is not the only part. If we see the design world as entirely under the control of profit motives and rapid fashion cycles, we become disheartened, believing that design that responds to broader conceptions of human need and desire is just a "nice idea" that is out of reach on a practical level. One of the best responses I have seen to this feeling of skepticism and disempowerment is from the Social Design Site. In this wonderful 7-minute introduction to their project and to “social design,” this international and interdisciplinary crew assert that “We cannot NOT change the world” – everything we do changes the world. Everything makes the world different, re-designs the world.

I love this part: “We are living in a very complex world, and in everything we do, whether we are aware of it or not, we constantly shape it. We as people are constantly acting in relation to other people, and by doing so, each and every one of us creates the world we live in.” This is a pretty simple observation, yet it reminds me that we so often look at the world as “done,” already made by the people who run governments and own cranes and build bridges, tunnels, roads, buildings, appliances, clothes, and computers. Especially for people with disabilities, the world seems to be made by others, others who likely do not have much imagination about body types, sizes, strengths, and abilities in mind. For me, the “right to design” is about seeing the world as an unfinished design project with still a lot of spaces to slip a hand in and fiddle with the machinery.

Well, that's about as manifesto-y as I can get. I think this blog will vary widely in scope, examining the high-fancy-fluffy design world as well as world news and politics for questions of design and inclusion. I am new to blogging in this formal way-- please comment if you're reading and have questions, critiques, or just want to say hi.

- First, it is kind of a question. Do we have a right to design? That is, do we have a right to designed things that fit us, that work well, and that are comfortable? When is bad design a violation of civil rights or human rights? A sociologist met recently pointed out to me that current disability law is one of the only official avenues of citizen complaint about poor public design. Even twenty years after the ADA, though, these questions are somewhat unresolved in the terminology of “reasonable accommodation.” I think of the “right to design” as a question, a provocative idea that prods us to ask what rights are, and also how design works to provide or block access-- not just to buildings or places, but to experiences that we might define as part of citizenship.

- Second, there is “the right to design” as a verb. Do we have a right to design things, to demand to make our own world different? This part of the argument comes out of years of observing and participating in debates around sustainable, social, and universal design. A lot of designers want to integrate these alternative, progressive ideas into their practice, but they can’t because their clients are not interested, considering these approaches to be unmarketable, or because they don't pass the tests of contemporary aesthetic or intellectual design practice. I, too, have often fallen into the rut of pessimism, thinking when I see a really great prototype or student design project, ‘well, that’s great but it will never get made.”

The way design appears in our current world is as commerce. Design is fashion, is consumption, is the latest desired object. This is indeed one part of design, but it is not the only part. If we see the design world as entirely under the control of profit motives and rapid fashion cycles, we become disheartened, believing that design that responds to broader conceptions of human need and desire is just a "nice idea" that is out of reach on a practical level. One of the best responses I have seen to this feeling of skepticism and disempowerment is from the Social Design Site. In this wonderful 7-minute introduction to their project and to “social design,” this international and interdisciplinary crew assert that “We cannot NOT change the world” – everything we do changes the world. Everything makes the world different, re-designs the world.

I love this part: “We are living in a very complex world, and in everything we do, whether we are aware of it or not, we constantly shape it. We as people are constantly acting in relation to other people, and by doing so, each and every one of us creates the world we live in.” This is a pretty simple observation, yet it reminds me that we so often look at the world as “done,” already made by the people who run governments and own cranes and build bridges, tunnels, roads, buildings, appliances, clothes, and computers. Especially for people with disabilities, the world seems to be made by others, others who likely do not have much imagination about body types, sizes, strengths, and abilities in mind. For me, the “right to design” is about seeing the world as an unfinished design project with still a lot of spaces to slip a hand in and fiddle with the machinery.

Well, that's about as manifesto-y as I can get. I think this blog will vary widely in scope, examining the high-fancy-fluffy design world as well as world news and politics for questions of design and inclusion. I am new to blogging in this formal way-- please comment if you're reading and have questions, critiques, or just want to say hi.

Saturday, June 7, 2008

disability and creativity sites of interest

The Missability Radio Show A WGBR-Boston radio show about disability and creativity. I love the whimsical and crafty aesthetic on this website and need to catch up on some radio shows on it ASAP. So many creative projects worth mentioning after just a few minutes on the site.. a Walking Stick Cosy Competition, an Etsy store, and much more... the use of old-time radio/entertainment aesthetic is apt for radio stuff, of course, but also seems to subvert the freak show history of early 20th century pop culture.

The Missability Radio Show A WGBR-Boston radio show about disability and creativity. I love the whimsical and crafty aesthetic on this website and need to catch up on some radio shows on it ASAP. So many creative projects worth mentioning after just a few minutes on the site.. a Walking Stick Cosy Competition, an Etsy store, and much more... the use of old-time radio/entertainment aesthetic is apt for radio stuff, of course, but also seems to subvert the freak show history of early 20th century pop culture.(image from Missability.com is of a handpainted cardboard sculpture of an old-time radio with red stripes atop a table covered with a handmade quilt that reads "Missability")

Also via Missability: Pimp My Guide, 2 videos on YouTube about customizing guide dog harnesses.

Access Hacks. I first saw this link-filled, fact-packed post from Liz Henry's blog somewhere out in cyberspace, and since have followed her links to a bunch of other places, including...

Gearability, a blog by woman named Marty, who writes about caring for her stepfather as well as having her own health concerns. The blog discusses everything from electronic calendar use in a nursing home to wheelchair cupholders. As an avid reader of sites like Ikea Hacker, I really dig how she seems to see every product, material, gadget out there as fodder for redesign and customization.

On a non-DIY note, fans of Wallace & Gromit must check out these Creature Discomforts PSA spots from British TV.

a world without stairs?

I recently met the pioneering disability historian Paul Longmore at SF State, a true pleasure not only because his work on disability history has been so important to my learning, but because he talked to me for 2 hours about my project, asked all kinds of useful questions, and sent me on my way with a notebook full of notes and thoughts. Anyway, one thing he mentioned as we were talking about design, accessibility, universality, etc, was that the facilities director at SF State is entirely committed to universal design. When they started a renovation project for the library recently, and the architects came in to show their plans, the guy apparently took one look at the entrance they proposed and said (something like), "no, that won't work-- we don't do stairs at SF State."

It got me thinking after the conversation-- is an accessible world a world without stairs? Universal Design promises spaces designed for all, and advises, when possible, to avoid separate entrances and pathways for people using wheelchairs, walkers, etc. So a gently sloped entrance, or maybe an understory at ground level and an elevator, are preferable to a main entrance stair and a side ramp. In practice, the main thing this means is reminding architects to do away with the small, unnecessary sets of stairs that might make an otherwise pretty accessible place or building inaccessible (like 2-3 stairs on a park path or in front of a house or building). But what about as an entire design strategy? A few thoughts...

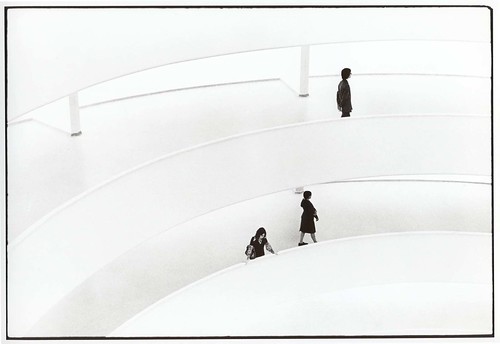

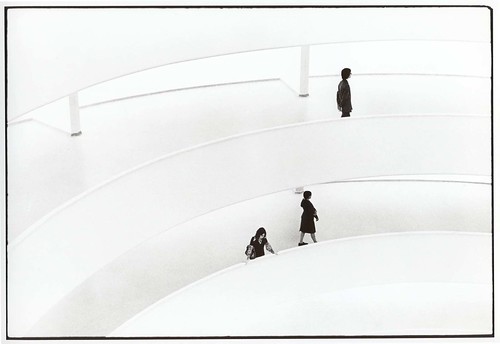

- The first thing that pops into my head is: is the Guggenheim in NY, completed in 1959, accessible? Or-- more precisely-- is its principal design focus, the long spiral ramp around an open atrium, universal?

Photo by ghougham on flickr.

(Image: a ghostly Guggenheim. Two long ramps sweep across the black-and-white image, with three small figures seen, one on the top ramp and two below.)

John Hockenberry describes the Guggenheim as "the most spectacular (if not the largest) indoor wheelchair ramp in the Western Hemisphere... Frank Lloyd Wright's personal gift to me and my manual titanium-frame wheelchair" (NYT, 1995). Was FLW aware of this angle-- or unconsciously aware, having lived through all of the 20th century, with polio, 2 wars, etc?

by Unstudio, & via Core77 Clogger. Image: architectural rendering of Unstudio's Mercedez-Benz Museum in cross-section, with ramps encircling the building to connect concrete-slab floors.

by Unstudio, & via Core77 Clogger. Image: architectural rendering of Unstudio's Mercedez-Benz Museum in cross-section, with ramps encircling the building to connect concrete-slab floors.

The Brooklyn Museum's renovation a few years ago put a new ground-level entrance hall below the grand temple-like stair of the original Howe and Lescaze building.

Image from Architectural Record

Image from Architectural Record

(Image: The Brooklyn Museum, a classical temple-style building complete with Greek pediment and Corinthian columns. Below the column facade is the new entrance, an open glass arcade at ground level.)

Entering gives the feeling of going through a catacombs, with heavy brick arches supporting the building, an apt sensation for the entrance to house of collections. I think the driving principle in the redesign was to make it more accessible in a community sense-- not the mansion on the hill, but a Brooklyn Museum that is open to Brooklyn. There are a lot of nice metaphorical angles to the idea of all of us getting in at the ground level. Shame is that they included a stepped atrium to get down slightly below street level-- the side paths are step-less, but the design misses its chance on the world without stairs.

Photo by ghougham on flickr.

(Image: a ghostly Guggenheim. Two long ramps sweep across the black-and-white image, with three small figures seen, one on the top ramp and two below.)

John Hockenberry describes the Guggenheim as "the most spectacular (if not the largest) indoor wheelchair ramp in the Western Hemisphere... Frank Lloyd Wright's personal gift to me and my manual titanium-frame wheelchair" (NYT, 1995). Was FLW aware of this angle-- or unconsciously aware, having lived through all of the 20th century, with polio, 2 wars, etc?

- The long descending ramp is a common theme in museum design, for example at the prize-winning Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, completed 2001.

by Unstudio, & via Core77 Clogger. Image: architectural rendering of Unstudio's Mercedez-Benz Museum in cross-section, with ramps encircling the building to connect concrete-slab floors.

by Unstudio, & via Core77 Clogger. Image: architectural rendering of Unstudio's Mercedez-Benz Museum in cross-section, with ramps encircling the building to connect concrete-slab floors.The Brooklyn Museum's renovation a few years ago put a new ground-level entrance hall below the grand temple-like stair of the original Howe and Lescaze building.

Image from Architectural Record

Image from Architectural Record(Image: The Brooklyn Museum, a classical temple-style building complete with Greek pediment and Corinthian columns. Below the column facade is the new entrance, an open glass arcade at ground level.)

Entering gives the feeling of going through a catacombs, with heavy brick arches supporting the building, an apt sensation for the entrance to house of collections. I think the driving principle in the redesign was to make it more accessible in a community sense-- not the mansion on the hill, but a Brooklyn Museum that is open to Brooklyn. There are a lot of nice metaphorical angles to the idea of all of us getting in at the ground level. Shame is that they included a stepped atrium to get down slightly below street level-- the side paths are step-less, but the design misses its chance on the world without stairs.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

odd (and old) links about how designers try to figure out who they are designing for

- Designing for the Senior Surge Wall Street Journal shows designers at GE wearing giant rubber gloves and glasses with scratched lenses to show how they try to understand the needs of an aging population in appliances. The new features they come up with-- a faucet that taps on and off, a double oven that fits into a single-sized space and has easier to open double doors-- are dubbed "aging-friendly" but would clearly benefit anyone (the double oven also seems like an energy saver since it separates a single-meal section from a section "big enough for a 22-lb turkey").

- via treehugger way back in 2006: Eco- and UD House demonstration by Panasonic also had designers using goggles to simulate visual impairment. Design features include unified standards for color and type size to enhance usability, as well as rounded furniture edges, wide threshold-less doorways. Some of the "sophisticated digital devices" also have voice guidance-- something I wish I had to teach me how to dress my second life avatar.

-

hello interweb

I am starting this blog to try to keep track of links, images, thoughts, etc about design, rights, and particularly the intersection between disability issues and design. I am in the early stages of a dissertation on how designers and users tried to improve everyday spaces and objects to make them more functional for a range of physical abilities, both prompted by rights legislation and not, during the second half of the twentieth century (focusing on the decades leading up to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990). That means things like custom cars, lighter and more flexible wheelchairs, and architectural accessibility, as well as "universal" design in buildings and products so that everyone can use them. This project comes out of several years of studying socially- and environmentally-conscious design; ultimately I am interested in how the built world responds to social change (or fails to).

A note about accessibility: when I use images in this blog I will describe them as best I can for text-only readers. I am new to this practice (though with art history training I should be better at it!). Please tell me if you have any problems reading this blog, for this reason or any others. I am new to blogging in general, so I genuinely appreciate constructive criticism of any kind.

A note about accessibility: when I use images in this blog I will describe them as best I can for text-only readers. I am new to this practice (though with art history training I should be better at it!). Please tell me if you have any problems reading this blog, for this reason or any others. I am new to blogging in general, so I genuinely appreciate constructive criticism of any kind.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)